The Queen’s University of Belfast | The Institute of European Studies | European Liaison

Publications

Dealing with Minorities – a Challenge for Europe

by Michael Breisky, Ambassador of Austria to the Republic of Ireland

The heirs of multinational Empires

According to many historians, Europe’s Golden Age should be seen as the decades following the Congress of Vienna in 1814/15. Indeed, over thirty years of almost complete peace and no major wars for a whole century make this judgement understandable. If we look at the map of Europe drawn up at the Congress, we see there three major powers of multinational nature: they are the Empire of the Hapsburg Monarchy, Czarist Russia and the Ottoman Empire. Looking at today’s state of affairs we note that the Hapsburg Monarchy has disappeared and today’s Russia and Turkey have been greatly reduced in their territories.

What happened to the rest of the area belonging to these three major players? Well, their territories are now divided up by 23 sovereign countries, most of them new ones, and this number still leaves out Russia, Turkey and the new countries in the Caucasus and Central Asia. Four of the 23 – Finland, Austria, Greece and Italy – are already members of the EU and the remaining 19 aspire to follow sooner or later.

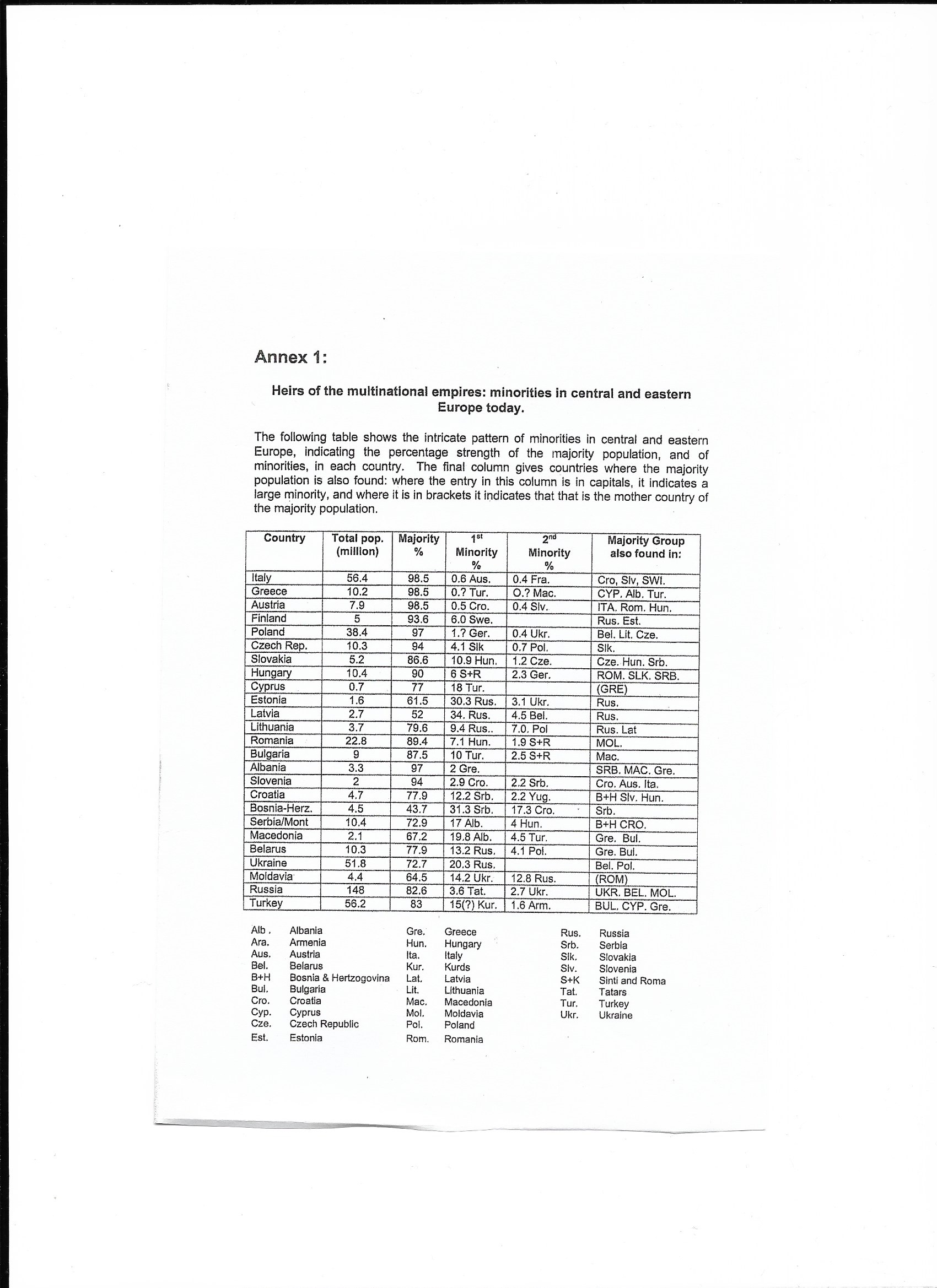

Looking more closely at these 19 countries in the context of minorities, one can see the following:

- in all of them, there are significant national minorities, making up several percent of the country’s population and/or constituting the majority in at least one area of settlement, however small; practically all the 19 countries have more than one minority on their territory;

- in 15 of the 19, the minorities are larger than any of those the EU has seen so far, amounting to 10% or more of the population (this is the case in 6 former Soviet and 5 former Yugoslav States plus Cyprus, Romania, Bulgaria and Slovakia); in 5 countries the dominant population group even sees its own majority questioned (Estonia, Latvia, Moldova, Bosnia and Macedonia);

- 17 of the 19 see themselves as the motherland of ethnic groups in one or more of the other European countries; largest of these dislocated peoples are the Hungarians in Romania, Slovakia and Serbia; the Albanians in Serbia and Macedonia; and the Romanians in Moldova;

- all this still does not consider the situation in Russia; before the collapse of the Soviet Union, scientists in Moscow counted 79 potential conflicts in the Union, 46 in the Caucasian and Central Asian areas; 20 of the 23 borders between Soviet Republics were identified as potential crisis points.

Admitting that these figures for the central and eastern European countries are much higher than for western Europe, what makes the situation so special? True, problems with national or religious minorities of political relevance are also to be found in all of today’s EU member states. But their history is a stable one; leaving apart the multi-cultural situation crated in recent years in many affluent countries by peaceful and mostly economically motivated immigration, here, in western Europe, basic ethnography has remained unchanged for more than 1200 years, the migration of Normans and Vikings and the plantation by Scots and English un Ulster being the exception to the rule.

In eastern Europe, however, things are quite different. Much of the leopard skin like pattern of ethnography in the Balkans is owed to the resettlement of areas depopulated during the Turkish Wars in the 17th and 18th century. And, further north, we had the events during and immediately after the 2nd World War: millions of Jews killed by the Nazi Holocaust, millions of Germans and Poles, hundreds of thousands of other nationals expelled in the name of a new order – all this still being felt as a heavy mortgage on today’s agenda. So the main differences are the higher figures and continuous lack of ethnographic stability in eastern Europe. What makes the situation even more touchy in the central and eastern European countries is:

the long – if not total – absence of democratic traditions, in particular the rule of law;

the ideological vacuum, created by the collapse of communism and being filled today to a large extent with old-fashioned nationalism.

Two symptoms demonstrate the situation in central and eastern Europe:

- statistics on the size of individual minorities are extremely unreliable and differ sometimes by tenfold, depending whether the central government or minority representatives are counting; the development of this statistical gap is a good indication of the state of affairs regarding the minorities in question.

- nearly all states in question refuse to do their homework in history. Their own sufferings are being taught and discussed at length, but their own wrongdoings are still taboo. Considering the fact that today’s minorities in a given state were partners or co-nationals of yesterday’s oppressors and that yesterday’s oppressors were, just the day before, the ones being oppressed themselves, it is easy to guess that hatred and distrust are still alive.

One does not need to look at Bosnia or Kosovo to see the dangers of such a situation. Minority questions are matters of national identity and, therefore, highly emotional. the case of the civil war in Northern Ireland and the bombings in South Tyrol during the 1960s show that democratic institutions alone are not enough to keep the use of force at bay. And even if bloodshed is avoided, disputes in minority affairs are always dangerous and apt to get out of control. In my own country, for instance, the rather minor question of putting up bilingual road signs in areas inhabited by the small Slovenian minority in Carinthia in the early Seventies led first to unlawful demolition of these road signs by German speaking Carinthians, invoking some sort of angst, then to a severe crisis with Slovenia and all of Yugoslavia, and finally to considerable damage to the general Austrian image abroad.

Now imagine the situation the EU is going to face if a new member state from central or eastern Europe with little democratic tradition were to have difficulties with minorities. Apart from the probability that in some states this difficulty might involve much more emotional dynamite than road signs – and let us hope no real dynamite will be involved – we have to think of the repercussions this would have on the very complex and delicate relations that go along with EU membership. Not only would this affect relations between member states directly involved, but these difficulties would in all likelihood be transmitted like a virus to other areas and particularly to common institutions of the EU.

This may seem exaggerated at first sight, but let us not forget two things. First, democracy and market economy may or may not be morally good things, but what made these systems so successful and essential to European integration is their unmatched ability to give, take and digest a vast multitude of information; these systems fail, however, if based on wrong or dishonest information. Second, most minority problems are not tabled openly and directly; they arise rather from matters that are apparently quite technical, the minority context being discretely hidden or even imagined. For example, how could one have imagined outside South Tyrol that the formal change of the legal status of the Italian railway system from an entity under public law to a 100 percent state-owned company would be interpreted as a serious threat to job chances of the Austrian minority? So we are likely to see genuine or imaginary problems being brought to Brussels under the cover of seemingly inoffensive technical matters. Thus, negotiations in the EU, often difficult and complex enough, would get hidden agendas, and the whole process of open bargaining would be distorted.

What could be done about that? Well, I think nothing could beat a systematic and energetic approach to the wide field of legal and political minority protection. The Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) has given increasing attention to this matter, particularly at its Copenhagen Conference on the Human Dimension in 1990. Later on, France has rightly recognised the dangers of minority issues in the context of the Balladur Plan. The Central European Initiative, a loose form of cooperation between Austria, Italy and most central and eastern European countries has come out in 1994 with an Instrument for the Protection of the Minorities. And in February 1995 the European Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities was opened for signature; it came into force in February, 1998, and it has been, up to August, 1998, ratified by 21 states.

This convention is a major breakthrough regarding the formulation of legal principles in the field of minority protection; before, we had only politically agreed standards that were legally not binding. By declaring the protection of national minorities an essential element for stable and democratic security in Europe, such protection goes beyond the interest of individuals and becomes from now on an objective for state policies in Europe. Thus, the protection of any minority as a whole is now to have a legal quality; the convention does not imply, however, the recognition of collective rights to self-determination, not even in its mildest forms of autonomy.

So what is my diagnosis?

In view of the dangers the EU is going to face with minorities from central and eastern European countries, can this be enough? I can hardly think so. But before I carry on, let me refer briefly to the terms of reference of what is going to follow. First: my theories remain within the area of political discussion and – maybe – reason, but I certainly do not suggest that they reflect today’s international law. Second: although most of my colleagues at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Vienna will go along with my opinions, they do not necessarily represent Austria’s official views.

Most important is the observation that every state needs – similar to Rousseau’s famous contrat social – something like a contrat national establishing consensus by all national groups of citizens to give voluntarily full allegiance to their state; it is not necessary that such contrat national should be explicitly laid down in a country’s constitution, but in many central and eastern European countries it seems to be absent even in its most rudimentary forms. As long as this is the case, minorities – always preoccupied with their identity and status – will feel that they are object rather than subject in their state, even if the constitution of their state should grant them full protection; and the majority group in that state will distrust them. Hidden agendas are seen everywhere by both sides – one side fearing annihilation and the other secession – leading to the dangerous distortion of frank communication in national and international forums.

But does not democracy make such a contrat superfluous? I do not think so, and history seems to imply even the opposite: during the European Golden Age of the 19th century, ethnic minorities fared relatively well with the autocratic Ottomans and Czars – as they did even again, relatively speaking – during Stalin’s years of terror. And in the Hapsburg Empire, the fate of the Austrian minorities – and even more so the fate of the Hungarian minorities – seems even to have deteriorated after the introduction of democratic reforms 1867.

Therefore, it might be useful to dwell a little on unavoidable tensions between minority protection and the idea of democracy. Generally and in the long run, the probability of choosing wisely is attributed to decisions that have the more or less explicit backing of the majority of people. This has become such a dogma that most people would also attribute a greater probability of wisdom to opinions and decisions based on 50.01 percent of the vote than to an opinion shared by 49.99 percent. Mathematically, such reasoning comes very close to sheer nonsense. No, the superior value of democracy is not the infallibility of its vote, but the chance to change one’s mind a little later and correct mistakes at the next vote. With this reasoning we can establish the definition of a minority: it is the smaller of two or more groups of people that cannot be expected to change their mind on matters of importance to their society. I think this definition reflects the ‘inside’ of man better than so called objective criteria, and this might help later on with my ‘therapy’.

The other observation of my ‘diagnosis’ concerns the state of mind within minority and majority, as long as this contrat national is absent. As I am going to elaborate, there are serious matters of identity at stake, and identity matters are known to be hyper-emotional. Now, maybe you remember from neurophysiology that the rational (left) side of the human brain is virtually blocked as long as the emotional (right) side of the brain is severely excited. You have to keep this phenomenon in mind in order to understand why it should be possible that two ethnic groups or traditions, having much, much more in common than what separates them, forever continue to ignore reason and to be at each other’s throat.

And why should these ethnic or cultural differences be seen with such high emotion? I think for the simple reason that everybody, once he adopts a national or cultural identity, does so in the belief that he is choosing an identity that is clearly superior to all others around. Hitler’s followers in and outside the Third Reich were the last ones to profess this superiority aloud and we know the disastrous consequences, but does not every national group or tradition believe in Providence, History or simply Darwinism to have picked them as the mystical chosen ones? And don’t they have – now please tick – valiance, endurance, virtue, religion, beauty, humour and the arts on their side to prove it? I think even the people of tiny Liechtenstein or San Marino believe in their superiority, although they are smart enough not to say it openly. Of course, with most people this process of adopting a superior identity happens quite innocently during early childhood at a pre-rational stage, so there is not much we can do about. But in the classical context of minorities – as opposed to the situation of the ‘new’ minorities caused by economically motivated individual migration, a situation I shall revert to separately – we see this superiority of the own group being constantly denied, even ridiculed between grown-up neighbours. Maybe this phenomenon is even worse for the majority: its people must feel deeply offended that the ‘generous’ offer to the minority to adopt the majority’s superior identity is steadfastly refused. And all that should not make one emotional?

It should be emphasised, however, that this psychological pattern applies only to traditional forms of minority conflicts. With the so-called ‘new’ minorities in western Europe and North America, mostly people that have immigrated to their country of residence individually, fairly recently and for economic reasons – the typical Gastarbeiter and his family – the psychological situation is basically different: here, the minority shows a clear interest in integrating with the majority. True, in most instances the minority would also prefer to maintain its original identity; but in any case the new minority regards the majority rather positively and much more rationally than emotionally (unless they sense a strong rejection by the majority). By contrast, the majority people tend either to ignore altogether the existence of a ‘new’ minority or to resent them vividly. Very often this resentment is the consequence of uncertainties concerning their own identity: the sheer presence of an alien identity seems to demand an answer to the essence of the majority’s own identity, and if a hollow pluralism of eroded values should render such an answer impossible, deep emotional insecurity would make all aliens appear like hostile intruders. Keeping this kind of reaction by the majority in mind should also be useful in the context of classic minority policy: it demonstrates again that the amalgamation of cultural identities is a risky thing and that these matters should never be swept under the carpet of liberal progressiveness.

Leaving the situation of new minorities apart, the problem seems to be: while fairness and prospects for long lasting peace would require some sort of a contrat national, and while its realisation would require some sort of self-determination, a therapy involving the latter would arouse the most explosive emotions; and it should, therefore, be discarded as a devilish cure.

Settling the issue of majority rule

My therapy would be to put all conceivable models of minority protection on the table, explain the pros and cons and then persuade the majority to let the minority have its choice. Should the choice be self-determination in its various stages, even in its most radical form of secession – so be it, but only step by step and making sure that the last step of secession can take place only on a distant day in the future, when the difference between minority and majority group and their respective identities will be seen mainly as a matter of diverging rational interests, having lost its previous contentious emotions. But is this not sheer utopia? Not quite, but a lot of work lies ahead.

Even before discussing the specific needs of a minority, one should look for reasonable agreement on the basic requirements of minority protection. First there is the constitutional problem of reconciling democracy with minority protection; there I see no alternative to the rigging of the goalposts of majority-rule. This can be done in two ways. One would be to take some matters out of the usual democratic game and deal with them – more or less by Diktat from a superior hierarchical level – in such a way that members of the minority would have more rights than their fellow citizens (e.g. the constitution requiring normal legislation to take account of the exclusive interest of minorities); with a dynamic understanding of equality in mind, this approach of superimposed regulations should be seen as an effort to counterbalance the minority’s lack of quantity by additional legal quality. The other way would be to reduce the size of the playing-field in such a way that new boundaries make the minority become the majority in a smaller area – a concept leading to democratic autonomy in its various forms.

Both alternatives have inbuilt advantages and disadvantages. The first one I would describe as being more direct and static, while the second would work rather indirectly and be more flexible; which would again give the latter advantages in the long run. There is, however, a drawback with autonomy: minority protection by autonomy would, at least in practice, amount to the recognition of collective rights – and this might easily be interpreted as the first step towards self-determination, clearly implying the risk of eventual secession. Autonomy is therefore a highly emotional topic.

Although fairness, flexibility and long-term considerations would speak in favour of a cautious preference for the autonomy model, there are, however, cases where objective circumstances would make territorial autonomy – and even more so the exercise of classical self-determination – extremely difficult, if not pointless; be it that the minority has no well-established area of settlement (as is the case with the Roma and Sinti); be it that the minority is extremely thinly scattered throughout all of its area of settlement (giving it no hope of becoming the majority anywhere); or be it simply the fact that there is no established majority group because three or more groups live in the same area (as it is the case in Bosnia). In these instances, strong elements of minority protection by Diktat could become unavoidable.

Reality is more complex than any theory, however, and requires in most instances a combination of both models. If well conceived, super-imposed models could very well have some niches of autonomy, and inversely, quite a lot of Diktat could be found in models that build on autonomy. Take, for instance, the models successfully introduced by the Hapsburg Empire to the provinces of Moravia and, later on, Bukovina in the early years of this century, where one finds a combination of separate electoral colleges for every ethnic group and autonomous powers attributed to them. This model should still today be of particular interest to the large Roma minorities I have mentioned, which have no well established area of settlement.

Therapy by self-determination without emotion

But if autonomy and self-determination should ideally enjoy preference, how could one approach the second basic problem of emotional dangers?

To the minorities one would have to say: ‘Sure, the day of full self-determination may still be far away; but there is no reason to despair. As long as you stick to peaceful means, all your options remain open. You were able to keep your identity in previous hard times when you were on your own, and now in addition to your own strength you have also the protection of all the political and legal instruments designed by the CSCE, the EU and the Council of Europe. And the EU will not accept new members with minority problems remaining wide open. But mind you: if you want the exercise of self-determination by secession, it may be the climax of nationalist debate, but it is no end in itself; and like other forms of climax, its aftermath may produce sadness’.

And to the majority groups in states one would have to say: ‘Forget the days when for reasons of economy or security it was in the interest of a state to have the largest possible combination of territory and people; in the EU things are different, a small member state with an homogenous society will have more influence than a large society fighting its own divisions. The granting of territorial autonomy for your minorities may be a good occasion to review your constitution from the point of improved efficiency – subsidiarity is today’s catchword. And if you play your cards well and address your minority openly, history teaches that the minority will not only loose interest in unreasonable forms of self-determination, but it will also subscribe to the contract national and become a genuine asset to you.’

So it is all about finding the right balance within a system of rational competition, where the majority argues in favour of integration for the sake of efficiency of the common state, and where the minority asks for the necessary requirements to safeguard and exercise its identity. In other words, rational interests would have to compromise with emotional interests – a situation needing the element of time and step-by-step approaches in order to cool unavoidable emotional steam to safe temperatures.

The first element of the job would be legal work; a maximum of measures for the protection of minorities, outlined in the various European Conventions mentioned before, would have to be implemented. Unless the minority should prefer to leave the issue there and desist from collective rights, one would then have to establish the different stages of autonomy and self-determination that are available – from cultural to territorial autonomy, comprising executive and possibly also legislative powers; and then further on to federal state, confederated state and finally to secession – and to agree to the principle that the more radical stage should not be attempted unless the lesser stage had enough time to demonstrate its insufficiency. That means one would have to exercise self-determination several times, going through rising degrees of autonomy (or internal self-determination) before eventually arriving at secession.

Still within the legal work, special attention would have to be given to institutional cross-border links between the minority and the state – if there is one – that is considered as its linguistic/cultural/ethnic motherland. The minority’s desire to move or abolish political borderlines will be greatly reduced if this borderline does not stand in the way of the minority’s continued (or re-established) cultural integration with the motherland. Let me give you an example. For the survival of the Austrian minority in Italy it was not only essential that South Tyroleans had the chance to get third level education at Austrian universities – as nobody could finance a fully fledged German speaking university in South Tyrol – but also the voluntary return of South Tyrolean graduates to their home area had to be safeguarded by a system of mutual Austro-Italian recognition of degrees and university diplomas.

The second element would be ‘applied minority psychology’. There we would have to work particularly hard on the sense of superiority which seems to persist on both sides of classic minority conflicts. We would have to teach at schools and in the media that such superiority is a pre-rational phenomenon; not bad in itself as long as it is needed only in early childhood for the forming of allegiance to a group identity, but dangerous and even stupid later on. We would have to explain the merits and the limits of group identities and national allegiances, mostly by putting them into the correct historical perspective of developing solidarity with the weak. And we would have to learn that the many prejudices against other groups – as they are in most cases the basis for the alleged supremacy of one’s own group – are little more than a thick coat of emotions around a tiny core of rational information. To give you an example: we Austrians referred to Italians in times of war and crisis as treacherous, cowardly and unreliable people; Italians considered us at the same time to be brutal, uninspired and stubborn. Today we are good friends and Austrians praise Italian charm and flexibility, while Italians admire Austrian order and reliability. What we see there is a tiny element of genuine information, i.e. Italians tend to be more pragmatic than Austrians, and a thick coat of fluffy emotions, tasting bitter one day and sweet another. I am sure this pattern will apply also to other forms of national prejudice, and that teachers, journalists and politicians will lead the way to overcome them within reasonable time.

Analysis of fear must also be the object of minority psychology, and in particular fear caused by ignorance of the other side’s intentions. Much can be done by issuing long-term policy documents on the state’s intentions and the minority’s aspirations, as a follow-up to the contrat national. Much fear, however, derives from the past and its misconceptions, particularly common in central and eastern European countries. Again to follow Austro-Italian examples: a great one is to put historians from both sides together and to let them rewrite history books and edit them jointly; and a lesser one you find in the Dolomites, where properly guided tours to the Italian and Austrian military cemeteries and trenches of World War I teach you the common misery of the poor guys that fought a European civil war. Military glory withers quickly in such an environment.

Another lesson for this kind of psychology would be the introduction of self-irony into this rather humourless world of minority affairs. Just imagine, for instance, an important European prize, awarded every year to a school for identifying the most ridiculous inscription on a monument built to glorify the supremacy of any one nation or group.

A framework for self-determination

But one day, once this process of down-scaling national emotions is well established, there would have to be the chance to exercise self-determination. How should this day be defined? I think such a day must be set many years in advance, and there should also be general understanding of the procedures for exercising this self-determination. Switzerland and Canada, two states with long-standing democratic traditions, have each set within their own constitutional framework good examples for such procedures that should be considered landmarks on the international scene.

In the mid-Seventies, Switzerland had to handle the secession of a French-speaking part of the Berne canton and its subsequent establishment as the new canton of Jura. This was done by a very elaborate procedure of federal, regional and multiple local voting, designed to find the fairest possible solution and to establish the ideal borderline between the cantons.

Only in August, 1998, Canada’s supreme court spelled out in advance how the country might legally and peacefully handle the secession of Quebec. It recognised the right to such secession and the obligation of other participants in the Canadian confederation to recognise such a clear vote of the Quebequois, but it also limited the right to proceed unilaterally to secession. Instead, both sides would be required to negotiate their new arrangements in good faith. The refusal by one party to negotiate would seriously put at risk that party’s assertion of its rights; if the refusing party was the seceding entity, it would jeopardise its standing in the international community, from which recognition as a sovereign state ultimately arises; and if the confederation should demonstrate `unreasonable intransigence’ in negotiations, other governments would be likely to recognise the sovereignty of the seceding part.

I think the Canadian judges have correctly hinted at a system of reward and punishment which should strengthen the process of confidence-building in all cases of self-determination. There would, for instance, be international pressure to concede self-determination by secession to a minority much earlier should there be misbehaviour on the side of the majority group; and self-determination would be postponed if the minority were to blame for such things. In any case, I think the European Parliament should not allow new members into the EU, unless they are fully committed to the idea of self-determination without emotions.

For the minority, I think the guaranteed option of full self-determination will be much more valuable than its exercise. It is quite likely that there will be a lot of cases where self-determination will result in autonomy, and in particular territorial autonomy with self-government in a wide range of matters. But much of it will coincide with general devolution of powers to regional and local authorities, a development I consider to be unavoidable, as an ever more complex world will require national parliaments and governments to limit the number of issues they handle, and to allow for devolution instead.

Yes, there is a theoretical risk that self-determination would neither stop at autonomy or even co-federation, and that we might have more new and predominantly small states. But even that would not be the end of a prospering Europe. Let us just think of the Holy Roman Empire from 1648 to 1806: it had 300 de facto sovereign member states, living quite peacefully – the few wars of that time were forced upon them either from abroad or from the largest member states; and their main problem, the many custom borders, would not rise anew, thanks to the European Single Market.

But anyway, I don’t think we would witness much secession or many changes of international borderlines. The first reason is the cost of sovereignty. The overheads of sovereignty are quite considerable; as an example, wealthy Luxembourg finds it difficult to administer its membership in the EU without technical assistance from Belgium and the Netherlands. Similarly, even reunion with the motherland would increase costs, mostly political costs related to the minority-within-the-minority-syndrome. As minorities usually have to share their area of settlement with members of the majority group, the latter would itself become a minority in the event of the former’s full independence or reunion with the motherland. In theory, this new minority could also claim self-determination, only to suffer a little later itself secession from an even smaller sub-minority. But in practice and much sooner than later, such a Russian doll-like sequence of events would, by its sheer ridiculousness, call for a more balanced approach. And while thinking about a change of borders, the first minority might consider that its motherland might not be very eager, at the same time, to import a new minority. Finally, once a minority is well treated by the country of residence and while enjoying support from the motherland, it will very soon learn to pick the cherries from both cakes – and the minority will not easily give up such a situation.

To prove the success of consensus in autonomy, may I again refer to South Tyrol. In 1993, one year after the Austrian minority had given their agreement to the formal closure of the conflict pending before the UN – a conflict that had seen many dead, bombs and bitter arguments about self-determination – an opinion-poll investigated the state of mind among Tyroleans and Italians living there. This poll showed that the major preoccupations for both groups were pollution and crime, and that none of their major concerns had anything to do with minority problems. In other words: fears that autonomy would increase the appetite for secession are, if properly handled, unfounded.

So I am convinced that Europe and all majority groups have nothing to fear from this concept of self-determination without emotions. And nothing should keep minorities from working quietly for a state of affairs, where the borderlines separating them from their kinsmen on the other side are reduced to little more than pencil lines on the map. Once this state of affairs has been achieved, the emotional dangers will have disappeared, and we might readily leave it to the perfectionist, whether he should reach for the india rubber or not.

What I have said so far would amount to the basic elements of a European policy on minority affairs, with a much-needed emphasis on the psychological mechanics of this topic. I think it is now high time to verify these insights in the real world of minority issues. But before doing so, a brief explanation on the relativity of success in these matters seems to be necessary. The overriding experience is: the more successful the model, the less you hear about it.

The ideal model would be the one where you don’t hear anything at all about the minority, because it does not even consider itself a minority. And indeed, this is the case, for instance, with the Celtic Romantsch in the south-east of Switzerland. They have got rid of all the disparaging connotations of the word, and they see themselves rather as the fourth and smallest language group in Switzerland, nevertheless equal in status to the German, French and Italian speakers. Almost silent success stories of official minorities would be the Swedes in Finland, the German speakers in Denmark and Belgium, the Danish in Germany and the French in Italy. But without temptation one cannot become a saint, and I think these minorities and their states did not have to overcome many temptations – probably because there were no realistic alternatives available.

So I would prefer to look at minorities that have a high risk of conflict and that have – together with the respective majorities – eventually coped reasonably well. And indeed, there is a model that looks very similar to my theoretical one; it was elaborated in lengthy negotiations by two sovereign governments and has been approved by the respective parliaments and, more importantly by an overwhelming majority of the people concerned. Basically, it involves the calming of extremely violent emotions and the protection of the respective identities by a system that builds more on super-imposed measures than autonomy. The model favours, very imaginatively, peaceful coexistence and cooperation on both sides, but nevertheless – and this I consider the most important feature – the option of the eventual exercise of democratic self-determination, even by a change of international borderlines, is firmly established. The only drawback to this model is the fact that there has not been enough time since last Good Friday to implement it, here in Northern Ireland.

…and some answers from Tyrol

This means we have to down-scale our expectations a little if we want to find models with a good performance record. I think it will not come as a big surprise that the model I want to discuss in more detail concerns the fate of the Austrian minority in Italian South Tyrol. It is not possible to explain the enviable progress of this Austrian minority during the last 30 years without referring to the enormous plight this people had to suffer during previous decades; sufferings inflicted on them mainly – but not exclusively – by Italians. Whenever I mention Italian wrongdoings, please be aware that they refer to past generations. Austria is happy to have today wholeheartedly and unreservedly friendly relations with Italy – government and people, and that Austrians, whenever they plume themselves on South Tyrol, should also pay their respects to the far-sightedness of some former Italian leaders, like Aldo Moro, Giulio Andreotti and Gianni De Michelis, and not least to the generosity of the Italian taxpayer.

South Tyrol’s population was almost exclusively celtic up to the time of the great migration in the fifth and sixth century AD, when the thin layer of Roman rule (established only in 15 B.C., i.e. after Britain) was washed away and Germanic settlers occupied most of the area. Since 952 formally part of the Regnum Teutonicum, various feudal territories on both sides of the Brenner Pass were in 1248 amalgamated by the Count of Tyrol, and this entity was a little later on peacefully acquired by the Hapsburgs in 1363. And so all of Tyrol stayed Austrian for the next five and a half centuries, until the end of the First World War, when the parts of Tyrol south of the Brenner Pass – South Tyrol proper and the so-called Trentino – a predominantly Italian speaking area of similar size – were annexed by Italy.

The annexation of predominantly German speaking South Tyrol was a reward from the victorious Allied Powers to Italy for entering the First World War on their side. Tyroleans and Austrians continue to consider this act as extremely unjust and a blatant violation of the right to self-determination, as it had been promised at that time by US President Woodrow Wilson. Figures speak a clear language: at the last Austrian census of 1910, there were slightly less than 3% Italian speakers and roughly the same number of Ladinians – the descendants of the celtic aborigines – and more than 90% German speakers.

And almost immediately after the annexation, the plight of the Tyroleans began. Some of the oppressive measures were introduced by the democratic government in Rome, but with the seizure of power by the Fascists in 1922, things turned from bad to worse. Any kind of German tuition became punishable, all German speakers were thrown out of public office, and their leaders imprisoned or sent into exile. German sounding names were Italianised, inscriptions on tombstones changed and even the speaking of German was forbidden. Contacts with the next of kin in Austrian Tyrol were severed, and many agricultural estates – particularly the ones close to urban areas – were nationalised, to make way for heavily subsidised new labour-intensive industries and housing estates for the labour force. The latter were exclusively Italians from southern regions, ushered into South Tyrol in their thousands with the clear Fascist purpose of changing the cultural and ethnic identity of the region.

But even with these measures, for the Fascists the Italianisation did not proceed fast enough. So once Austria was wiped from the political map by the Anschluß in 1938, Mussolini agreed with Hitler to settle the Tyrolean affair for good. All German speakers of South Tyrol and all Ladinians from the surrounding area were called to decide: either to opt for formal German nationality and to emigrate to Nazi Germany – or to forfeit all claims to their accustomed identity. An enormously bitter dispute between supporters and opponents of this option arose, and by the end of 1939 a very impressive 86% of the South Tyroleans had opted for emigration. This result is attributed to various factors, most importantly the risk for those who remained that they would be resettled, sooner or later, somewhere else in Italy or its colonies. Furthermore, there was the treacherous propaganda that the Führer might be emotionally moved and convinced to change his mind by arranging for a return of South Tyrol to the Reich, if all of its people would opt for Germany. The beginning of the Second World War slowed down the procedures for emigration, and it came to a complete stop in 1943, roughly at the same time Mussolini founded the Saló Republic and German military forces took over the civil administration of South Tyrol. But at that time already 76,000 South Tyroleans – roughly one third of the Optanten – had left their home.

After 1945

The end of the war in May 1945 gave reason for new hope. The Austrian Republic was re-established, and although its population was very close to starvation and the war-torn country occupied by the Allied forces, its leaders – themselves just released from Nazi concentration camps – immediately claimed the exercise of the South Tyrolean’s right to self-determination. The Allied Powers looked quite favourably at it up to the spring of 1946, when a foreboding of the Cold War became visible. Italy was more valuable to the west than little Austria, and by allowing South Tyrol’s return to Austria, one would have alienated all Italians and weakened the democratic parties’ fight against the big Italian Communist Party. So in spite of a petition for reunification with Austria, signed by a large majority of the total population of South Tyrol, self-determination was ruled out. (It appears that Italy’s Prime Minister Alcide De Gasperi worked against South Tyrolean self-determination in order to secure his own political basis. Himself a Trentino, he was faced in 1945/46 with a strong separatist movement in his home province, disenchanted by Rome’s centralised rule. It could only be placated by promising the people of Trentino a position within Italy not inferior to the status of South Tyrol). In the end, the only concession granted to the Tyroleans was autonomy within Italy; and so an Austro-Italian agreement on South Tyrol was annexed to the Italian Peace Treaty, negotiated in Paris by the Allied Powers and Italy in September 1946.

This annex, signed by Prime Minister De Gasperi and the Austrian Minister for Foreign Affairs, Karl Gruber, and later on referred to simply as the Paris Agreement, became the Magna Carta of the South Tyrolean model. Its stipulations had little binding force – typical ‘soft law’, reflecting Austria’s very weak international standing at this time. But at least it was an agreement under international law, and if interpreted in a benevolent way, it would contain all elements for the effective protection of a minority. Italy, however, did not interpret it in such a way. Sure, some things changed for the better, in particular the reintroduction of German speaking schools and the taking back of some 25,000 Optanten; but apart from dragging feet on the implementation of other very important clauses, like the use of German in court and in dealings with the police, up to the early 1990s, the stipulations for South Tyrol’s legislative and administrative autonomy were blatantly abused when the Paris Agreement was transformed in the Italian constitution. By adding the populous Italian speaking province of Trentino to the territory of the autonomous region, Italy’s Prime Minister De Gasperi secured a rock solid Italian speaking majority within the region, thus perverting its meaning. And in addition to this legal abuse, migration from Southern Italy to the new industries in South Tyrol continued to be pushed by the government.

Austria did not take this development lightly. But up to 1955 and the conclusion of the State Treaty and the departure of the four occupying Allied Forces, she was herself object rather than subject in international policy and had to resign herself to toothless protests. After 1955, however, South Tyrol became the most important issue in Austrian foreign affairs; at the same time the situation in South Tyrol worsened, when Rome made arrangements for a new wave of Italian immigration to South Tyrol. In accord with the South Tyrolean leaders, Austria pressed in particular for the dissolution of the injurious Autonomous Region Trentino-South Tyrol. When Italy continued to refuse Austrian demands to implement the Paris Agreement, Austria’s new Foreign Minister, Bruno Kreisky, took a bold step and in 1960 presented the whole question of the Paris Agreement to the General Assembly of the United Nations.

It was a bold step, because the UN of that time – still long before the peak of decolonisation – was for several reasons in no mood to accommodate any initiative directed against Italy: one was Italy’s NATO membership and the other, Latin American members’ concern for their many Italian immigrants. And among the UN members not belonging to these two groups, there were a few only that did not have minorities that were even worse off than the South Tyroleans. But then enter Ireland and Conor Cruise O’Brien who, as a member of the Irish Delegation to the UN happened to be, at that time, Chairman of the General Assembly’s Special Political Committee, which had to deal with this matter. Under his imaginative and energetic guidance it was possible, first, to win the support of other former British countries and then to engage a clear majority of the Assembly in a seemingly procedural approach, which eventually even found consensus: the General Assembly qualified the whole Paris Agreement – including its Article on autonomy – as a measure for the protection of the South Tyrolean minority and urged Italy and Austria to find peaceful means for the solution of the problem. Henceforth Austria had a solid mandate to expose Italy’s handling of the question annually to this world forum.

For the next year Italy preferred to ignore the issue. In the summer of 1961, however, violence struck. Tyroleans from both sides of the border started to bomb and blow up institutions of Italian infrastructure, mostly pylons. Efforts to avoid bloodshed were evident and succeeded at first, but suffered badly in an obvious escalation of terror and counter-terror, which cost many lives and spread also to Austria. In the autumn of 1961, the UN adopted a similar resolution to force negotiations – and finally, Italy began to move into the right direction. For face-saving reasons Italy insisted, however, on proceeding on two levels. On the basis of `voluntary concessions of purely domestic nature’, Rome negotiated with the South Tyroleans material improvements to the autonomous region, and in bilateral negotiations with Austria, designed end the dispute still pending before the U.N., formal guarantees for the `internal’ improvements were sought. Italy seemed to offer a choice: either little material improvement with relatively strong international guarantees or substantial improvements with a weak political guarantee only.

The package and the calendar of operations

I shall spare you details of some very long discussions, but nine years later, in autumn 1969, the deal was done. On the one hand, the South Tyroleans, led by their charismatic Silvius Magnago, agreed to a package of 137 very detailed measures covering most of their grievances, to be implemented by constitutional laws and decrees, national laws and administrative acts. On the other hand, Austria agreed with Italy on a `calendar of operations’. The calendar must be seen as agreement on a zip-like procedure: the measures of the package were implemented by Italy in phases, and after each phase Austria had to take a formal step in the direction of the closure of the dispute. This end was to be achieved not only by a corresponding declaration to the UN, but also by ratification of an Austro-Italian agreement, which allows for a submission of the Paris Agreement to interpretation by the International Court in The Hague.

And indeed, with this agreement of 1969, at very long last, for the South Tyroleans things began to change definitely to the better. True, the Autonomous Region Trentino-South Tyrol was not abolished, but its powers were reduced to almost zero – a typical example of Roman face saving. In turn, South Tyrol – officially the Autonomous Province of Bozen – was endowed with substantial legislative powers, including agriculture and forestry, crafts and professional training, trade, tourism and regional transports, public housing, health, environment protection and promotion of industry. In other matters of particular relevance to the South Tyroleans, such as the use of the language, schools, and also public employment and minimum residence for establishing voting rights, the South Tyroleans could achieve consensus with Rome for national laws that met their interests. And most importantly, there were generous provisions for the financing of this autonomy.

Naturally, there were drops of bitterness in the South Tyroleans’ cup of joy. In accordance with the Italian legal system, all the new promises concerning constitutional laws became effective only by government decrees describing their implementation in a more detailed form; and procedures for these decrees took extremely long – the last one came into force only by 1992, that is 18 years after the date one had agreed to in 1969! Some of these delays were caused by the continuous instability of Italian governments; with an average lifespan of 10 to 11 months only, most cabinets were already gone before their agenda would have allowed to deal with South Tyrol. And then the South Tyroleans were very shrewd negotiators when – in accordance with the package – they were consulted by the Italian government and their experts about these decrees. Made distrustful by their experience of the last 70 years, they argued with Rome for ages about every single iota, and in the end they were able to achieve concessions by Rome that went beyond the original package.

The positive atmosphere created by the agreement on the package coincided with an economic boom in South Tyrol, building mostly on areas dominated by German speakers, like tourism, small scale industry and agriculture – the latter heavily subsidised by the EC. The immigration by southern Italians came to an end, and many Italian civil servants on mission in South Tyrol returned to their homes further South once public office was opened again to the South Tyroleans. As a consequence, the census carried out every ten years showed a reversal of trends in the population mix: Italians, who amounted to just under 3% in 1910 and had thereafter continuously risen to 35% in 1961, stagnated in 1971 and then fell to 29% in 1981 and 27% in 1991. The German speakers increased correspondingly (the Ladins continued to be fairly stable at 4%).

In spring 1992 the last measure of the package was put into force by Italy. The whole procedure of implementing the package was formally reviewed by Austria; additional constitutional and international guarantees were given; and the dispute, pending at the UN since 1960, came at long last to a formal end. At the same time another dimension became apparent: negotiations for Austria’s accession to the EU made progress, and hence one could with reasonable confidence expect the day, when the borderline between North and South Tyrol on the Brenner Pass would be reduced to little more than a pencil line on a map. If you remember my reference to an opinion-poll of late 1993, showing that none of the greater political preoccupation in South Tyrol had anything to do with minority problems, then, I hope, you will finally agree with me: voilá, a rare example of success in a classic case of minority problems!

Analysing the South Tyrol model

The Paris Agreement continues to be the political and legal basis of this success. Politically, it still has repercussions on the question of self-determination: while full self-determination must be seen as an inalienable right of South Tyroleans themselves, Austria cannot claim the exercise of this right on their behalf and at the same time insist that Italy stick to the Paris Agreement. From a more important legal point of view, this agreement contains all the essential elements of minority protection I have described in the first half of my lecture:

Article 1 refers to the balancing of the continuing minoritarian situation by the provision of `superimposed structures’;

Article 2 rigs the playing field of majority rule by the introduction of legislative and administrative autonomy;

Article 3 provides for a day-to-day lifeline between South Tyrol and Austria in various areas.

While painting today’s situation of the South Tyrol in these friendly colours, and turning now to emotional aspects, one has to admit that the picture of a success story arises only at some distance. Of course there are still quite excited debates going on today and if you listen to debates at an average convention of moderate parties – be it the traditional South Tyrolean People’s Party with close to 90% of the minority’s vote or the local branches of the nation-wide Italian parties of the left and centre-left – you would still think that South Tyrol continues to be in crisis. Even worse if you listen to the Heimatbund, still asking for South Tyrol’s secession from Italy, or the local Italian parties openly acclaiming old and new fascism. The point I would like to make is that the emotional dimension of different identities cannot be suppressed, but must be put into a visible context. Therefore: yes, there are the many inciting and emotional Sunday speeches in South Tyrol, apparently needed by majority and minority in order to keep the essence of their respective identities on the level of consciousness and to avoid a non-European amalgamation of cultures; but the important thing is, nowadays, by Monday the emotional atmosphere has cooled down to the working conditions usually found around conference tables. So one could call these Sunday speeches the poetry of minority politics.

To put this kind of poetry into correct perspective was not an easy task for both governments in Vienna and Rome. Vienna had to make sure the South Tyrol issue was not overly emotionalised and then hijacked by splinter groups with nostalgic feelings for the Nazis. Later on, there was the additional task of demonstrating to the Italian speakers in South Tyrol the advantages they would have from enhanced cooperation with their neighbours to the north. Things were even more difficult for Rome: once the deal on the package and its guarantees was done, Italian governments, usually formed by very fragile coalitions, had to engage in face-saving exercises with regard to their predecessors wrong-doings, but without encouraging the Italian speaking hotheads in South Tyrol. Also the Italian civil service, mostly shaped in Mussolini’s era and extremely sceptical of any idea of de-centralisation, had to be kept at bay. To understand the situation of the Italian speakers in South Tyrol in the post-package era, one has to realise that they saw their own status suddenly turned upside down: up to the Seventies, they were the privileged ones, but now in the new autonomous province, they had to give up this status and live henceforth as a minority themselves. In the end all sides – governments in Rome and Vienna as well as the South Tyrolean People’s Party – seemed to follow a common recipe:

- to down-scale public debate on the issue, and in particular to give as little weight to megaphone diplomacy as possible; never ask for things you know the other side can never accept;

- not to contradict openly unrealistic demands by the hotheads of your own side, as long as these demands are lawful; and not to answer provocations by the other side’s hotheads;

- to have good and trustworthy personal relations between all political leaders involved, to be invoked only in moments of crisis, and to delegate most negotiations in matters of substance to less visible committees, not worrying too much about their time consuming procedures.

Elaborating on the last point, I would even add: don’t worry about extremely complicated procedures; as long as their outcome is fair and balanced, you have a good chance to divert looming dangerous emotions on to anonymous bureaucrats and away from real people. The handling of public funded estate housing and employment in the civil service are showcases for this approach: up to the 1970s both domains were almost exclusively reserved to Italian speakers. With the package there came the so-called Proporz, a system of allocating publicly funded housing and employment by national, provincial and communal authorities in proportion to the population mix of the last official census. This system was and continues to be highly bureaucratic, demanding from every applicant for jobs and housing under the Proporz proof of the linguistic group he or she declared at the last census, a prerequisite that produces even more bureaucratic red tape. But more importantly, this Proporz is effective.

In hindsight, the South Tyroleans’ leader, Silvius Magnago, seems to have applied a particularly effective scheme to handle emotions. On various occasions he managed to push questions of secondary importance to the forefront of political discussion, making them the lightning rod for boiling emotions. Once the debate was polarised around this bait-like secondary issue, it was easier to solve the primary question, and in its wake the secondary question was soon either solved as well, or openly stripped of its importance.

From a legal point of view, I would attribute the success of the South Tyrolean model to a good combination of overcoming minority status, and the institutional urge for consensus in the new statute of autonomy. To begin with the former, in matters of school and cultural affairs, neither German nor Italian speakers should have any reason to develop minority feelings; the statute of autonomy guarantees both communities – and similarly also the small Ladinian group – full autonomy, that is independence with separate administrative systems. In economic matters, South Tyrol enjoys a status quite close to a free state within Italy. And very important also is South Tyrol’s negotiating position in Rome. All changes to the statute of autonomy and to government decrees dealing with its implementation have to be deliberated in a Commission of Parity, where members of the South Tyrolean minority and the Italian majority are represented in equal numbers. To my knowledge, so far only one decision of this body was not arrived at unanimously – a precedent important in its own right.

Quite remarkable also are the measures designed to favour consent. Apart from the statutory presence of all ethnic groups in the provincial government in accordance with their strength in the provincial diet, I would like to underline the following two provisions of the statute of autonomy. Under its article 56, two thirds of the Provincial Diet’s representatives from one ethnic group can challenge any decision of the Diet at the Italian constitutional court‚ if they consider this decision to be contrary to the equality of rights pertaining to citizens from different ethnic or cultural identities. And more importantly, under Article 84, any discretionary provision by the Diet for financial expenditure can be challenged at the regional administrative court by a simple majority of representatives from one ethnic group.

At first glance, the `measures for overcoming the minority status’ should favour only the South Tyroleans, while the `institutional urge for consensus’ would have to be seen as an Italian speaker’s safeguard against being unduly dominated by a majority of German speakers. But reality is more subtle. Nowadays, autonomy also plays into the hands of the Italian speakers in South Tyrol. The two articles I have mentioned, designed to protect the Italian speakers, would appear to be unnecessary, as there has never been any occasion to apply them in practice. However, one could say that they have worked already by deterrence, obliging the majority in the provincial Diet to seek consent. And equally, one could argue that the principle of consent within South Tyrol has also eased relations between South Tyrol and Rome, as there is no reason to suspect any anti-Italian agenda. In this sense, the South Tyroleans were well advised always to allocate the important budgetary portfolio of the provincial government to an Italian speaker.

But how about the core elements of my theories on minority policies, the demand for a contrat national and the option of self-determination? Neither element is to be found in the Italian constitution, and it remains questionable whether multilateral conventions ratified by Italy – like the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights of 1966 – could be interpreted in this sense. I am convinced, however, that much of the psychological effect of such provisions was achieved when South Tyroleans had to wait so long for the complete implementation of all measures of the package, almost twenty years longer than originally stipulated. During this period, Rome continuously stated that all the remaining measures would be implemented soon; and indeed, there was, almost every year, a little improvement in the status of autonomy. In the end, encouraged by a slow but continuous outflow of `benefits’ from Rome to their province, and assisted by their new affluence, South Tyroleans found it easier to assess their situation rationally; and consequently, full self-determination, as the emotionally soothing long-range objective, was more and more moved to the back burner.

Conclusion

If everything is well in South Tyrol, can we close the file? Frankly, I do not know. There are visible challenges ahead that have to be mastered, like allowing South Tyrol to engage in European regionalism, in my eyes an area where we shall witness much more movement in future. Rome is sceptical, however, about this form of emancipation and very critical of enhanced regional cooperation among the three constituent parts of old Tyrol – North and South Tyrol plus the Trentino. Possibly, Italy fears a trend to self-determination or even secession similar to that proposed by the Lega Nord. Looking at it positively, I would say political questions are never completely answered, they just gain relief from the arrival of more urgent questions.

In this sense, the file concerning South Tyrol cannot be closed, but the survival of the Austrian minority in Italy does not figure among today’s urgent questions; instead, people with similar problems are invited to look into this file.